Musically agile maestro Davis bends to match iconoclastic Kissin’s Tchaikovsky with CSO

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andrew Davis; Evgeny Kissin, piano. Oct. 15 at Orchestra Hall.

By Nancy Malitz

The musicians of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra were “Semper Gumby” in a fascinating concert on short rehearsal that offered a look at what it means to be a pro in the classical music business. On Oct. 15 they performed a one-night-only concert featuring guest conductor Andrew Davis and the beloved Moscow-born pianist Evgeny Kissin in a Russian Romantic favorite, Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1.

I mean, how hard could it be, right? To put together two familiar works — Bach’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor and Stravinsky’s suite from his ballet “The Fairy’s Kiss,” followed by the Tchaikovsky concerto, which most musicians can play in their sleep.

All this, led by a conductor who has spent years in the opera orchestra pit dealing with the unpredictable real-time chaos of the typical grand opera performance. (Davis is music director of the Lyric Opera of Chicago and a veteran of the world’s opera and concert houses).

But Kissin’s interpretations are never off the rack, and it’s fair to say that the zip with which Davis and the orchestra began the Tchaikovsky is not what the profoundly individualistic soloist had in mind. You could feel this crack troop of musicians and their super-flexible leader snap to alertness when Kissin ignored what he had just heard and played those first famous chords with an added share of gravity, applying the brakes tout suite.

There was continued push and pull throughout. Whenever the pianist had an extensive time out, the musicians’ collective Tchaikovsky DNA re-emerged, and vice versa. If the results were hardly cohesive, there was excitement in witnessing what it means to adapt and improvise.

Through it all, Kissin offered a magnificent exhibition of piano playing at the highest technical level. To those impressed by Bishop’s knife trick in “Aliens,” I hope you have a chance to witness Kissin’s double-handed octaves someday. The pianist really is a marvel, and the crowd was raptly attentive, abruptly explosive in their ovation. How many times has Kissin played this concerto? Hundreds? One has to admire the non-conforming freshness of his approach, his enthusiasm for digging deeper. The slow movement was ravishing, a miracle of delicacy.

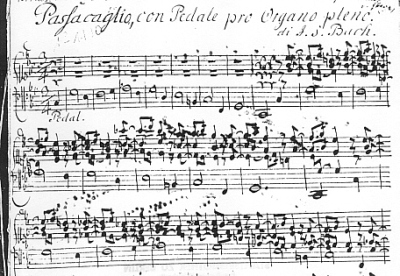

The concert began with another challenge: This particular orchestral version of the Bach’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor was not one of the better known arrangements, but rather one by conductor Davis himself. Bach wrote it for pipe organ, the king of instruments in his day.

In arranging keyboard works from previous eras, composers often strive to bring out inherent orchestral or vocal effects they think the original composer was wishing for, as if to fulfill its destiny. Davis seems to have had something else in mind. Bach’s chosen instrument was wondrous in itself, and Davis, an organ scholar, is clearly in love with its intrinsic virtuosity, its many ranks of sound and its unique combinatorial possibilities and expressiveness. His orchestration is rich in nifty effects that pay tribute to the pipe organ in all its glory.

In arranging keyboard works from previous eras, composers often strive to bring out inherent orchestral or vocal effects they think the original composer was wishing for, as if to fulfill its destiny. Davis seems to have had something else in mind. Bach’s chosen instrument was wondrous in itself, and Davis, an organ scholar, is clearly in love with its intrinsic virtuosity, its many ranks of sound and its unique combinatorial possibilities and expressiveness. His orchestration is rich in nifty effects that pay tribute to the pipe organ in all its glory.

From bar one — strings playing smoothly and with a soft front edge, their sustained tones etched by a pianist’s extremely dry, sharp staccatos that disappeared almost instantly from the sound mix — it was clear what Davis was after. Throughout certain stretches, you could close your eyes and think yourself at an organ recital. The effects were unusual and undoubtedly tricky to pull off. Passages that worked were brimming with savvy. The passages that didn’t left the impression of actors who were mouthing their words.

“The Fairy’s Kiss” was similarly up and down, but overall delightful. It was strongest in the third and fourth movements, a scherzo and a pas de deux saturated with color and sparkling with beautiful solos from assistant principal cellist Kenneth Olsen and the orchestra’s wind and brass core, buttressed by guest principal flute Mark Sparks, principal of the St. Louis Symphony, and guest principal oboe Elizabeth Koch Tiscione, principal of the Atlanta Symphony.

For the record: Kissin played three encores, hypnotic miniatures by Tchaikovsky, with the orchestra musicians remaining onstage. The numbers were the “Natha-Waltz” from his Op. 51 Morceaux, the Méditation in D from his Op. 72 Morceaux and “December” from “The Seasons.” It was a remarkable gesture for a soloist to offer so many encores, but it is actually not unusual for Kissin in this city. They love him here, and he obviously loves Chicago, too.

Related Links:

- Kissin returns to Chicago in recital Nov. 15: Details at CSO.org

- Highlights of the CSO 2015-16 season: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

Tags: Andrew Davis, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Evgeny Kissin